Knock for knock agreements (K4K) have traditionally been used in the oil and gas industry where projects are often high value and high risk. Other types of offshore projects, such as wind farms, are similarly high value and complex undertakings in often challenging environments. Knock for knock agreements are becoming more common for wind projects but not without some teething pains.

Knock for knock contracting – from offshore oil and gas to wind

Written by

Published 11 August 2024

What is a knock for knock agreement?

The main characteristic of a K4K agreement is that a party agrees that it will absorb any damage to its property or personnel without pursuing any recourse action against its counterparty. The provisions will be reciprocal and are therefore mutually beneficial to the parties. K4K agreements will apply irrespective of fault and will also generally contain mutual waivers and indemnities in respect of consequential losses.

In its simplest form, a visual representation of a K4K clause would appear like this:

A party will also protect its counterparty from the risk of claims falling within the scope of the clause by way of an indemnity. As such, whilst a party may be unable to prevent an employee bringing an action directly against its counterparty, the claim will ultimately be circular as it will fall back on the employer under the indemnity extended to the counterparty.

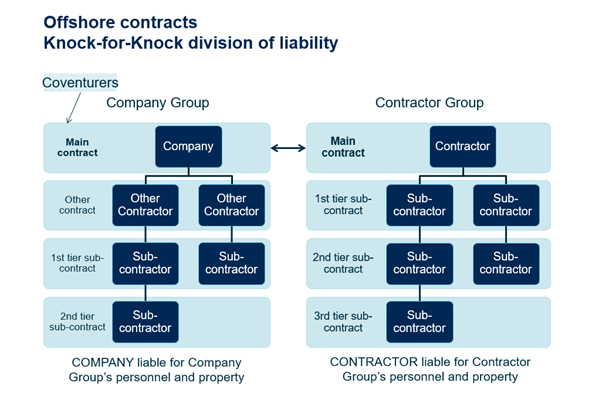

A K4K agreement will usually confer the benefit of the provisions beyond the contractual parties to a group of third parties who fall within a defined scope of companies and people on either side of the contract, most notably, employees and sub-contractors. There may well be further K4K provisions between the various commercial parties within the groups on either side so that the waivers and indemnities are similarly implemented in all contracts in the contractual chains, with the view that a loss stays with the party who has suffered it.

Why use K4K agreements?

Fault based liability is a fundamental concept for most, if not all, legal systems. So, why would a party be willing to waive rights of recourse against a contractual counterparty? There is a general acceptance that the reward achieved by participating in a project should be commensurate with the level of risk accepted. In the context of high value offshore operations, it would be uncommercial to expect a party receiving only modest remuneration to be willing to assume a disproportionately high risk. Using a K4K agreement, a party can be confident that they will have only limited exposure under their contractual arrangements in respect of their own property and personnel. This achieves certainty about the extent of the risk which they are assuming by participating in an offshore project and ensures proportionality. The party can then obtain insurance to cover their own interests. Comprehensive K4K regimes that are fully respected by all parties to a project increase certainty and may therefore reduce the scope of overlapping insurances or at least reduce the aggregate insurance premiums.

There is less risk of litigation and associated time and legal expenses when all risks are pre-allocated in the contract and the respective insurers pay losses incurred by their insured without recourse to another party who may or may not have caused or contributed to that loss.

Without the risk of litigation, there is a greater incentive for the parties to be transparent. This is likely to be beneficial in managing risk and improving safety, as well as preserving valuable commercial relationships in a limited market.

Components of a K4K agreement

A typical K4K will have at least two parts to it. In the first part each party agrees to assume responsibility for their own property and personnel. The types of claim that fall within the clause are clearly defined. In the second part each party agrees to indemnify the other in respect of claims for which they are responsible under the clause.

Responsibility for own property and personnel

Clause 14 of the SUPPLYTIME 2017 provides a good example of K4K provisions, particularly as the contractual exceptions have been narrowed down over the years so that it is closer to a pure K4K regime.

In an ideal world, the scope of any K4K clause should be as wide as possible to promote certainty. Consequently, over time, rather than simply identifying the contractual counterparties in K4K clauses, it has become common practice to extend the scope of the K4K clauses to include the property and personnel of related parties, e.g. as part of a Charterer or Contractor’s Group. For example, in SUPPLYTIME 2017, the definition of “Charterers’ Group” is expansive and includes the charterers themselves, their clients, co-venturers, contractors and sub-contractors and any employees, as well as combinations of these categories. Similarly, the “Owners’ Group” is defined to include the owners, their affiliates, contractors and sub-contractors and any employees. In broad terms, the aim of these provisions is to try to ensure that anyone other than the Owners who is on the offshore site for the purposes of the Charterer or Contractor’s business should fall within the K4K clause. Ideally the protection of the K4K clause is effectively replicated down through the different groups on back-to-back terms so that risk and exposure are broken down into more manageable chunks.

Defining the scope of K4K provisions

In signing up to a K4K agreement, the parties are contracting out of liabilities which they would have at common law. Under English law, there is a presumption that a party does not intend to abandon its common law rights. Careful drafting is therefore required to avoid any ambiguity which could defeat the purpose of the K4K clause by introducing the possibility of indemnity claims against contractual counterparties or related business partners.

K4K provisions commonly exclude claims arising from one of the party’s act, fault or neglect. They may also extend to gross negligence (a concept not recognised under English law), material breach of the contract and consequential losses. In other words, the K4K provision is intended to be a comprehensive allocation of risk leaving responsibility for claims with whichever group owns the property damaged or employs the personnel injured regardless of fault no matter how characterized.

Indemnity provisions

As a matter of English law, it is not possible to exclude liability for personal injury or death arising from negligence. This introduces the risk of a private individual within one party’s group pursuing a direct action against the other party for any personal injury or death, notwithstanding the K4K provisions. As such, a K4K clause will include additional indemnities to ensure that the responsibility for any such claims ultimately falls on the correct party.

In addition, there may be third parties in the vicinity who do not fall within either of these Group definitions, for example, the owner of a sub-sea cable in the area of the offshore operations. As such, to guard against the risk that one of the contractual counterparties ends up with an exposure to third party claims which have arisen through the other’s action, each contractual counterparty should ideally provide an indemnity in respect of third-party claims which arise from their own acts or omissions.

There is always the possibility that there may be an indirect exposure to a third party via the K4K indemnities. Drawing upon the first principle of maintaining any legal rights to limit, it is advisable to incorporate wording requiring the contract parties to maintain their legal rights of limitation when dealing with third party claims, such as:

“Where the Owners or the Charterers may seek an indemnity under the provisions of this Contract or against each other in respect of a claim brought by a third party, both parties shall seek to limit their liability as against such a third party.”

Insurer’s considerations and benefits of a K4K regime

A practical consequence of the indemnities is that, to minimise the risk of litigation and promote efficiency within the insurance arrangements, there is generally a contractual requirement for one party to be named as a co-insured under the other party’s insurance. This confers on the former the benefit of their counter-party’s insurance so that the insurer who will ultimately be liable can take control of the claim and deal with it as they see fit.

Where an underwriter insures more than one party as assured and co-assured and one party is exposed to liability arising from the other party’s actions, the underwriter cannot pursue a subrogated claim against the other party. Further, it is not uncommon for the insurers to be asked to waive any subrogated claim formally against the other party where they are named as co-insured. To avoid the risk that the scope of the waiver may be wider than intended, specific wording is required along the following lines:

“The Client shall upon request be named as co-insured. The Contractor shall upon request cause insurers to waive subrogation rights against the Client. Co-insurance and/or waivers of subrogation shall be given only insofar as these relate to liabilities which are properly the responsibility of the Contractor under the terms of this Contract.”

Without this qualification, the underwriters of one party may find that they are providing cover more generally to the other party and are unable to pass on liabilities which should properly rest with the other party’s underwriters under the K4K regime.

Is K4K suitable for offshore wind?

Another area involving a large number of the offshore contractors is the wind industry. Large wind parks are being developed with both fixed and floating wind structures with connecting subsea cables and connectors. The operations are familiar to the contractors, involving seabed surveys, foundation works, installation of monopiles and turbines and connecting it all together with cables on the seabed.

The leading companies in the early development of offshore wind were new to the marine industries and brought along a shore-based liability concept based on negligence. The mindset was, and still is to an extent, that the contractor is the one performing the installations and therefore must be responsible. This approach has been contested by the contractors and insurers who have lived with the knock for knock principle for decades in the offshore industry. Major oil companies (now energy companies) are also involved in the wind industry. Their participation, together with initiatives by Bimco with suitable contracts for the industry, e.g. Bimco Windtime, has made the knock for knock principle more common in the industry over time. Construction policies are generally taken out by the companies with full co-insurance for the contractors, but deductible levels are generally higher and responsibility for sub-deductible losses transferred to the contractors in the event of a claim.

Both for construction and maintenance of the wind, there is a demand for accommodation vessels and crew transfer vessels. These may operate in areas and jurisdictions where there has not previously been offshore involvement. Certain jurisdictions may not recognize knock for knock agreements with regard to personnel or there may be specific requirements for such agreements to be valid, such as German jurisdiction, where knock for knock provisions are only valid if there is an exception for gross negligence and wilful misconduct. There would further be a requirement that there has in fact been a negotiation, not just using a standard contract without further consideration.

Insurers, like Gard, who are familiar with K4K principles welcome the adoption in the offshore wind industry.

Conclusion

K4K contracts are an essential and enduring feature of offshore oil and gas production. Carefully drafted, they are accepted and favoured by insurers for their certainty in risk allocation. Tried and true for oil and gas, the expectation is that such arrangements will continue in alternative offshore energy generation including the installation and maintenance of offshore wind farms.

The author thanks colleagues, Kim Jefferies, Tore Furness, Teresa Cunningham and Torgeir Bruborg for their assistance with this article.