Gard has seen a worrying increase in fatalities and serious injuries from container ship fires this year. This article looks at what is driving the fires and the continuing efforts to address them.

Written by

Mark Russell

Vice President, Global Claims Lead, Safer with Gard

Are Solum

Vice President, Denmark

Published 18 December 2025

When we last reviewed container ship fires, we noted for the approximate 250 million container shipments a year, everything goes well most of the time. Nevertheless, when a single container fire does occur, the consequences can be increasingly severe.

The container sector is not the only one suffering from cargo fires – vehicle fires on car carriers and ro-ro ships, scrap and coal fires on bulk carriers are other examples. In this article we focus on container ship fires, because this year fatalities and serious injuries reached double figures. This is based on a review of nearly twenty fire incidents in Gard’s claim records so far in 2025. The tragic consequence for people appears to arise mainly from responding to fires which raises serious considerations for the safety of tackling container fires onboard. There are also other reasons to focus on container fires:

The environmental footprint from fires burning for weeks, cargo lost overboard and the processing of tens of thousands of tonnes of fire debris and contaminated firefighting water; with ships themselves sometimes ending up as a wreck.

Hundreds of millions of dollars for salvage and port of refuge services, extra cargo handling, waste processing and ship repairs; as well as losses in respect of damaged and delayed cargo and lost vessel use.

Lithium-ion batteries the main cause

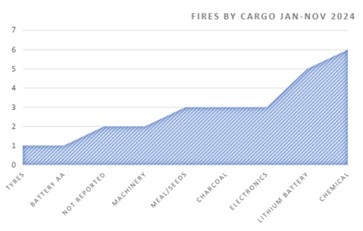

Whilst investigations continue, lithium-ion batteries appear to be the main cause of container fires on Gard’s books this year. This accords with growing numbers of cases identified by CINS from last year and cargoes of concern listed by the Cargo Integrity Group.

Fires involving lithium-ion batteries can be self-sustaining and may involve explosion of flammable vapour clouds, increasing the risks for responders. Even if they are not the source of a fire, when lithium batteries are involved, containing and extinguishing a fire will likely be made more difficult.

In some of the cases reviewed on Gard’s books, fires were contained thanks to swift and decisive actions of crew, as exemplified in this CHIRP report. Early use of container penetration extinguishing devices or the CO2 hold system avoided serious escalation. However, in over a third of cases, external assistance was sought by the ship. In some of those, salvors faced difficulties finding a place of refuge, increasing the risk to ship and environment. In another case a container that was due to be loaded exploded at the terminal.

In many cases, portable electronic devices were not declared as Dangerous Goods (DG). Fires involving lithium-ion batteries had cargoes variously declared as: "onboard chargers / non-DG / non-Battery," "EVA Case for tablet PC / non-DG / non-Battery", “Emergency bulbs”, “Mini Fans”, “Emergency bulb kit”, “solar chargers”, “chargers, phone cases”, and “mobile phone accessories”.

These apparent misdeclarations are complicated by Special Provisions in the IMDG code which exempt certain lithium batteries from the code’s Dangerous Goods (DG) declaration and other requirements. The exemption depends on limits for the battery energy and other criteria including packaging, notably to protect batteries from short circuits and damage that can trigger thermal runaway. In one fire case, lithium-ion batteries were found in electronic waste concealed within cargo declared as “mixed aluminum scrap”. Another involved used electric vehicles which were mis-declared as “cars” and not in accordance with Class 9 requirements.

In those fire cases with declared Dangerous Goods, one involved a Class 4 (flammable solid) chemical cargo. Another involved smoking in one of eleven containers of used electric vehicles, for which Gard has previously raised concern. This was quickly addressed in port and led to all containers being removed from the ship and detained by the authorities.

Cargo screening, inspection and carriage

As we wrote in 2018, tackling cargo misdeclaration is the first line of defence against container fires and the 2025 cases suggest that continues to be the industry’s main challenge. The container lines are addressing this head-on, with the World Shipping Council (WSC) launching this year an industry first digital cargo screening tool. It scans millions of bookings in real time using keyword searches, trade pattern recognition and AI-driven algorithms to identify potential risks. Alerts are reviewed by carriers and, when needed, verified through targeted inspections, which can now be performed more remotely. Seventy percent of global container capacity has already committed to the WSC’s Cargo Safety Program. It is hoped that in future iterations of the screening program, operators will be able to quickly alert each other when an unsafe shipment is discovered or an incident occurs. A wide and tight net is needed – an incident can reveal multiple unsafe containers from the same shipper in the supply chain. A rejected unsafe booking may also find its way onto another operator’s ship underscoring the need to share information about shippers of concern between operators.

Of course, the hope must be that by engaging with shippers, as DG teams at liner operators frequently do, shippers will become more compliant. Some operators are imposing contractual penalties for misdeclaration. Some even ban certain types of goods, notably used EVs, though experience from previous bans for example, calcium hypochlorite, suggests that a ban may inadvertently “encourage” misdeclaration because of fewer carriers and higher costs. CINS, the IG and other bodies continue to collaborate in publishing carriage guidelines, the latest this year fittingly covering lithium-ion cells. Container lines also collaborate in industry efforts to enable greater efficiencies in the exchange of safe transport documents from shippers that carriers can rely on.

IMDG code revisions also help by mandating provisions that lower the risks. A tightening of regulations for charcoal may already be paying off. It remains a cargo of concern from fire in previous years but has not featured in Gard cases so far this year. Work is also underway at the IMO, coordinated by the WSC, on the safer categorization of vehicles under the IMDG code.

Shipboard fire protection

With an estimated 200 million hazardous cargo screenings and complex supply chain challenges, unsafe shipments will slip through even the tightest net. That is why Gard’s 2019 container fire conference focused on what shipping companies can control – the ability of the ship and crew to detect and suppress fires. On increasingly larger ships, there is a greater chance of having one unsafe container onboard and it was clear that SOLAS fire protection requirements were not keeping pace. Regulatory work followed at the IMO and extra requirements currently under consideration include:

portable infrared thermal imagers for confirming and locating a suspected fire in a container

extendable water mist lances that can be activated by water flow at a safe distance so as not to require operator proximity to a container when it is penetrated (one lance currently required for new ships from 2016, with ships often equipped with a manual hammer)

fixed water monitors for ships designed to carry five or more tiers of containers on deck (mobile monitors are already required for such new ships from 2016)

water protection systems below the hatch coaming and pontoon hatches

Fixed water monitor onboard vessel

Fixed water monitor

Firefighting strategy is not something that would be regulated but deserves a mention given the growing number of fires involving lithium-ion batteries. The safety of manual firefighting is rightly under the spotlight and there is increased focus on early suppression of fires using fixed firefighting systems. Questions continue to arise as to whether the mindset onboard ships facing lithium-ion fires needs adapting more towards safe containment than firefighting.

Are measures going far enough, quickly enough?

The work of the IMO Fire Protection Correspondence Group continues and it remains to be seen what SOLAS changes will be agreed. Of concern is that the extra requirements outlined above would only apply to new ships from 2032. In one member state submission to the IMO, the cost of retrofitting four fixed water monitors on a 14,000 TEU ship was estimated at around USD260,000.

Concerns also remain for delays in fire detection, both above and under-deck. Fitting sensors to make around 40 million or so individual containers “smart” and to have them communicate with carrier systems appears some way off. On the ship’s side, there are several promising heat and gas detection technologies that would potentially buy crew vital time to try to suppress a fire.

In all of this it must be remembered that crew are not professional firefighters. Their efforts preserve the very things seafarers care most about – each other and their ship. No seafarer wants to experience a fire getting out of control to the point of abandoning ship. They deserve tools which give them a better and safer fighting chance, which is why the extra IMO measures are important. Some operators have made voluntary investments in those measures ahead of the SOLAS changes, but there are likely many more ships still operating with minimum statutory requirements. Several Classification Societies have developed additional notations for enhanced fire protection. These extend to hold flooding, which in Gard’s experience, is often a necessary measure of last resort due to the limited effect of CO2. However, the uptake of these notations appears to be less than 5% of the global containership fleet and mostly limited to newer larger vessels. The desire for a level playing field amongst shipping companies is understandable, but the long time needed for regulatory change should inspire alternative approaches. Cargo customers stand to benefit – many are affected even if lucky enough to only experience delayed cargo. Shouldn’t they be willing to pay more freight for better precautions against misdeclaration by other shippers?

Gard’s conference also raised questions about the lack of verification of shippers in the transportation of dangerous goods. Over a decade ago a member state proposed to the IMO that the function of “safety adviser” be incorporated into the IMDG Code. It is perhaps time to revisit the suggestion – shipping companies must have a Designated Person Ashore responsible for the safety of the ship – so why not the equivalent in respect of the safety of dangerous goods being shipped? Terminals and container storage yards also have a role to play. Often unsafe shipments sit for days before being shipped – a lost opportunity in the supply chain to neutralize risk.

The role of authorities

It is a rare case that rogue shippers end up paying for the consequences of misdeclaration. Gard continues to help members and clients pursue recourse actions with some success, but often shipper assets are dwarfed by monetary amounts claimed. Authorities have a role in making shippers more accountable. For example, in China mis-declared cargo causing serious injury or death can carry life imprisonment for the shipper. State accident body investigation into serious cases, however, is often absent. When investigations are done and reports released valuable lessons are often learned Investigation has even revealed a lack of sufficient public firefighting capacity in some ports and coastal waters.

It is also disappointing that some states that demand more from shipping companies are failing in deterring misdeclaration through routine inspections agreed at the IMO over 20 years ago. IMO guidelines for inspection programmes were extended in 2022 to targeting of undeclared or misdeclared DG units. The Cargo Integrity Group recently reported that less than 5% of 167 national administrations regularly submit public results to the IMO.

Conclusion

Container ship fires started to noticeably escalate in the 1990s when the largest containerships were around 8,000 TEU. At that time, in Gard’s experience, the most common cargos causing fire were calcium hypochlorite and barbeque coal. Today the ships are up to 24,000 TEU and lithium-ion batteries now appear to be a signifciant threat. With lithium-ion batteries now a fixture of global trade, the risk of high severity fires is unlikely to abate soon.

While industry efforts on many fronts continue to address the problem, the challenge is not only to prevent the next blaze, but to safely contain it before the cost in lives and livelihood climbs higher still.