Our first in a series of Gard Insights covering the topic of mental health of seafarers, discusses what can be done to break the taboo surrounding mental illness.

Published 23 October 2019

Seafarers live and work under more challenging conditions than most of us. They are exposed to an environment that stays with them 24/7 for the duration of their tenure on board the vessel. This Insight addresses some of the key issues that affect their mental health every day of their working lives while they are on board the vessel. Some factors can be controlled and others cannot. Knowing what can be controlled provides an opportunity to make the positive changes.

Before looking for solutions, it is important to understand what is considered to be a mental disorder. According to the WHO’s Fact Sheet, a mental disorder is generally characterized by a combination of abnormal thoughts, perceptions, emotions, behaviour and relationships with others. The disorders include depression, bipolar affective disorder, schizophrenia, dementia and autism. Of all the disorders, depression is the most prevalent with over 300 million people affected worldwide. Symptoms of depression include a prolonged period of sadness, loss of interest or pleasure, feeling of low self-worth, loss of sleep or appetite and lack of concentration. At its worst, depression leads to suicides. Through this Insight and the series that will follow, we hope to show that it is sometimes possible to prevent it going that far.

Gard Facts When we look at Gard’s data from 2010 to 2019 and compare the number of deaths due to injuries and illness, we see a declining trend from 2013. However, for mental illness and suicide, we see that the numbers have remained somewhat unchanged. Over the last 10 years we have seen 65 deaths, 32 cases of mental illness and an average of 4.6 suicides each year. The graph below illustrates the trends that we have seen in our P&I mutual portfolio. The numbers do not include missing seafarers who are not counted as suicides so the suicide rate may be underreported.

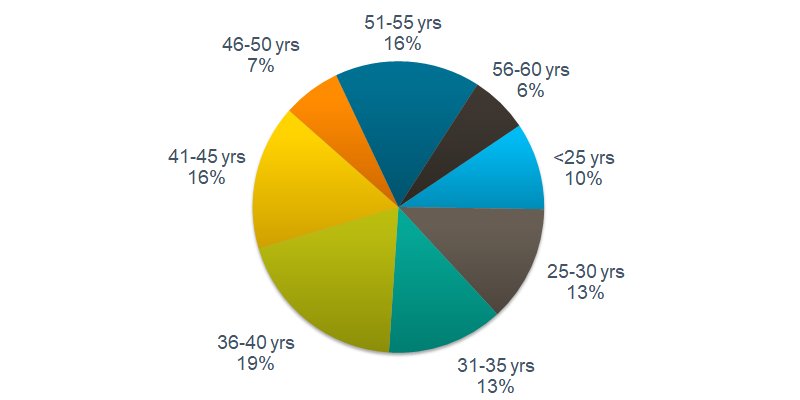

Suicides, by age group

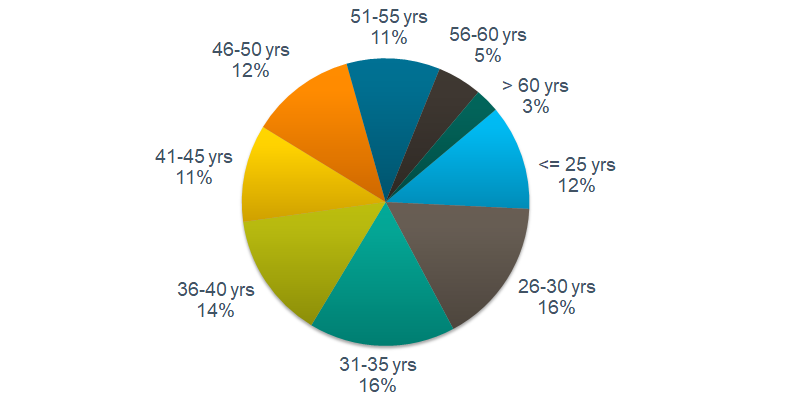

Mental illness, by age group

The distribution of mental illness and suicides by age groups suggests that all age groups are equally vulnerable.

Looking at the above charts, it is evident that the cases of mental illness are equally distributed across the age groups 26 to 40 years and we see more suicides in seafarers above 36 years when compared to their younger peers.

This is an important finding as it raises questions whether the industry is currently too focused on younger seafarers as “ being susceptible to mental disorder or suicide as they find the seafaring life very hard in the beginning.” It is evident we need to address mental illness across all age groups..

Challenges dealing with mental illness

The first and perhaps greatest challenge is the social stigma associated with mental illness. A person with mental illness is often assumed to be no longer employable. The main reason for this assumption is the lack of understanding of the illness and the lack of awareness of how it is treated and managed. Mental illness, like most other illnesses, is curable. Considerable research has been done on the recovery of people suffering from mental health issues. One such study was done by the Australian Health Services and Support which found that with proper treatment, most people were able to recover and lead a normal life with no further reoccurrence of the illness.

The study included people suffering from anxiety, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia where the recovery was over 80% on average. This story is worth sharing as it shows that mental illness is not necessarily permanent. This also shows that when someone is suffering from such illness, they will be able to work normally once they have received the appropriate treatment. These kind of success stories are important to bring mental health issues into perspective and to help remove the age old social stigma around mental illness.

Another success story is the implementation of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). This was largely successful in Zimbabwe when the government trained so-called grandmothers in providing this therapy to people in need. Some six months after its introduction, only 13-14% of people seen by the grandmothers continued to have symptoms of depression or anxiety, compared with about 50% of those who received the standard treatment, in which a nurse talked to them and prescribed medication.

There are several other research studies that have proved the effectiveness of psychological intervention, both short and long term. The question is whether shipowners are willing to share these success stories in office meetings or safety meetings on board ships. When it comes to addressing the social stigma, social awareness is equal to acceptance. The more we discuss the issues in meetings, the more awareness is generated and hopefully acceptance of the curability and normality of mental illnesses.

Another difficult challenge with mental illness is identification of the illness and the availability of care. Seafarers, just like the general population, are not trained to identify another person suffering from depression or anxiety. Furthermore, due to lack of awareness, care is generally limited to isolating the person with the illness until the vessel reaches the next port of call. Despite its prevalence, there is very little understanding of how best to assist the individual suffering.

Gard has worked with the Red Cross (Singapore) to learn about Psychological First Aid (PFA). In short, PFA is a supportive and practical first response given to people in emotional distress during or immediately after a crisis. Any lay person who is trained in PFA can provide emotional support and PFA can help to prevent the onset and development of mental illnesses.

The Red Cross has a lot of experience in interacting with individuals with signs of mental illness. Their experience with PFA has been generally positive as it is quickly effective. Their recommendation is to look for the intial symptoms of mental illness such as irritability, anxiety, absenteeism, or aggression towards colleagues and to intervene before it gets worse.

But who could provide the PFA on board a ship? The answer to this may be the senior members of the shipboard team. A common assumption is that cadets are the most vulnerable to self harm, however, Gard’s data shows that the rate of suicides is far higher among the senior ranks. Training only senior officers to provide PFA would result in no-one being able to administer PFA to those who might need it the most.

The care, or the first aid, has three basic steps,

looking for signs of stress,

initiating a dialogue with the individual by actively listening without being judgemental, and

providing practical help.

More details about PFA will be provided in one of the next Insights, where we will share the experience of a Gard claims handler who received training in PFA.

Recommendations

The issue of mental illness is a vast subject, Members and clients are urged to spend more time on understanding the problem.

As a starting point, it is important to accept that seafarers have the same challenges, feelings and motivations in their day to day life as anyone else. In addition, they have the challenge of being constrained 24/7 on board a ship for long periods of time and far away from friends and family. Their behaviour can be a response to the environment on board the ships.

Seafarers should be encouraged to talk about mental health to bring normality to the issue. Mental health should be discussed routinely in office meetings as well as safety meetings on board.

Providing the master or senior members of the shipboard team with PFA training is not sufficient, they need others to take care of them too.

The issue of mental illness is prevalent, there needs to be acceptance of this and it is important to increase awareness around it.

Mental health is an important component of physical wellbeing aboard ship. Depression can lead to suicide, a tragic loss of a life resulting from a treatable condition. It is crucial to break through the stigma which often forces seafarers to suffer their mental distress in isolation. It’s time to talk about mental health and treat mental illness with the same compassion shown to other health concerns.