“Not always afloat but safely aground”, or NAABSA, is used to describe ports where the seabed is suitable for the vessel to rest at low tide without damage to its hull. However, care is required when calling such ports to avoid not only damage to the vessel or delays, but also to avoid straining the commercial relationship between owners and charterers.

Written by

Published 24 November 2020

Introduction

The NAABSA phrase has its roots in commercial realities and disputes around the charterparty clause and the practice are not uncommon, especially when taking to ground is not anticipated by the crew. Gard as a P&I, Hull and Machinery and Defence insurer, handles claims and disputes under charterparties containing a NAABSA term with cases and inquiries coming from both our insured owners and charterers. We outline three case studies followed by discussion of the legal position raised and provide practical loss prevention advice.

Case study 1: Unanticipated sitting on the ground

Charterers nominated a load port in South America. The charterparty was on an amended NYPE 1946 form. It contained an express safe port/berth warranty. The NAABSA provision in the charterparty stated*“ unlimited NAABSA option for ECSA* [East Coast South America]”.

In their message containing the voyage instructions, charterers did not mention that the port is a NAABSA port. Local agent’s pre-arrival message, however, identified it as one but this was overlooked by the Master. The port authorities had not officially declared the port as NAABSA but the local agents were of the assumption that the said port was a NAABSA port for vessels above a certain size.

Loading of deck cargo started at 1530 hrs and around 1830 hrs the vessel started to list to the sea side. She had also moved laterally away from the fenders. Manual soundings were taken by crew and it was confirmed that vessel had touched bottom on the jetty side. Taking to ground had not been anticipated by the ship’s crew as the master had missed the NAABSA mention in the agent’s message. Furthermore, the company had no procedures in their Safety Management System (SMS) for vessels calling NAABSA ports.

The Master stopped loading and issued a letter of protest to the charterers and the terminal, holding charterers responsible for all loss, damage and expense suffered as a result of the vessel touching bottom. Charterers rejected the protest on the basis that touching bottom was “customary” at NAABSA ports. They further insisted to continue loading, but the Master refused citing structural strength and stability issues. The vessel refloated a few hours later, at which point the vessel was shifted to another berth at the Master’s request and loading resumed. Charterers put the vessel off-hire for the period that loading was suspended.

Although there was no water ingress into the ship, owners wanted to carry out an underwater survey, however it could not be carried out at the load port and was instead done at the discharge port. Indentation on ship’s bottom was discovered and this was confirmed by the inspection of the ballast tanks. No other significant damage was noticed.

What was the effect of the NAABSA clause in light of the safe berth warranty? Was the Master justified in discontinuing cargo operations and ordering the vessel to an alternative berth? Was the charterer entitled to take the vessel off hire when the Master discontinued loading and who ultimately bears the risk of the damage to the vessel?

Before addressing the specific questions raised by this scenario, we first consider NAABSA clauses in general. Then we look at procedural and practical considerations for both owners and charterers followed by loss prevention recommendations.

What is the legal effect of a NAABSA clause?

NAABSA clauses are usually incorporated to avoid charterers finding themselves in breach of the “always afloat” requirement in most charterparties where it is intended for the vessel to call at ports or places where, due to tidal conditions, she may touch bottom. NAABSA clauses in charterparties indicate owners’ acceptance that such an event may occur.

NAABSA clauses must be read in conjunction with the general warranty of safety in the charterparty. Therefore, if the vessel’s hull is damaged as a result of lying aground at a NAABSA berth, it may be possible to argue that charterers will have breached their obligation to nominate a safe port/berth where the vessel can lie safely aground. However, the success of such an argument will depend on a factual assessment of the characteristics of the berth. It must also be kept in mind that the master is required to exercise reasonable navigation and seamanship to ensure the safety of the ship.

NAABSA clauses must be considered within the wider context of warranties of safety of ports, berths, anchorages and places mentioned in a charterparty. They usually contain a warranty by charterers that the nominated ports, berths and/or anchorages a vessel is ordered to are safe. Depending on the particular charterparty clause, the warranty of safety may be express, or implied.

*Express warranties of safety *

There are two main types of express warranties: a warranty of absolute safety or a qualified one.

For example, an absolute warranty of safety can be found in the NYPE 1993 form. The reference to safe places would also include the vessel’s approach to the berth. The measure of safety in an absolute obligation is whether the dangers of the port or place could have been avoided by good navigation and seamanship. Some standard forms, such as the Shelltime forms (Shelltime 3 and Shelltime 4) contain a qualified warranty of safety, lowering charterers’ obligations to one of due diligence. This means that a nominated port or place would be considered safe if a charterer could have reasonably concluded, based on the known facts, that the nominated port or place was prospectively safe, at the time the orders to proceed were given.

*Implied warranties of safety *

Sometimes, the charterparty does not contain an express warranty of safety of a port or place to which a vessel has been ordered. In certain, narrow circumstances, the English Courts may be prepared to imply a safe port/place obligation into the charterparty. It is important to note that where a charterparty does not contain an express warranty of safety, but ports have been expressly named in the charterparty, whether as a list or described as a range between two specific ports, no warranty of safety will be implied into the charterparty. For a more general discussion on safe ports see our Insight on this topic and also on implied safe berth warranties.

Negotiating NAABSA clauses

It is important to consider the wording of the NAABSA clauses incorporated into the charterparties. Some charterparties may incorporate the BIMCO NAABSA clause. This clause is more comprehensive, and owners retain a reasonable right to reject charterers’ request to call at a NAABSA port. The clause also requires charterers to confirm in writing that a vessel will lie on a soft seabed without suffering damage and charterers must indemnify owners for any consequential losses suffered due to the vessel lying aground.

More common, however, are clauses which require owners to call at NAABSA ports, meaning that owners do not have the option to reject such an employment order. These clauses may name specific ports or refer to a range of ports where vessels are permitted to lie safely aground. Some clauses may be worded more broadly, referring to ports where it is customary for vessels to lie safely aground. These clauses do not usually include an express indemnity from charterers to owners.

There is no legal definition of what is “customary”, and the question of whether it is “customary” for vessels to rest on the seabed at a certain location is one of evidence. If vessels regularly touch bottom at a particular berth or place without suffering damage, this could be considered customary.

Turning to our case study, the NAABSA clause means that the Master cannot refuse the charterer’s order to berth at a location within the stated range provided the vessel can “safely” lie aground. The key word is “safely”. Thus, if the vessel is damaged due to the condition of the sea or riverbed where she touches, owners may claim for that damage unless the damage could have been avoided by ordinary good seamanship. Provided the vessel can lie safely aground and in a stable condition, the Master is not entitled to interrupt cargo operations and charterers may rightfully take the vessel off hire if he does so. The complications in the first scenario could perhaps have been avoided by better communication between charterers, owners and the Master. In the next section, we discuss what steps owners and charterers can take to ascertain the conditions and characteristics of the sea or riverbed, and other practical considerations for good seamanship.

Procedural and practical considerations

Shipowners or managers do not always have guidance on NAABSA calls in their Safety Management System (SMS) to which the crew can refer. As in our above case study, the actions taken are very much reactive after the vessel has touched bottom. The SMS should contain detailed procedures on the preparations needed and actions to be taken both by the crew and shore management when a vessel calls a NAABSA port. SMS procedures should generally cover the four stages discussed below. A simple checklist with the key points can assist crew members.

1. Before arrival at port

This is the information gathering stage. First refer to the NAABSA provisions in the charterparty and also the charterer’s voyage instructions. Then collect the information which can be provided by the sources on ground, i.e. local agents and P&I correspondent. Some of the things to look out for are:

Any official declaration by authorities recognizing the port as NAABSA

Nature of seabed and its topography to determine that the seabed is uniform

Minimum depths and maximum draft allowed

Date of last survey and dredging works carried out

Loading and discharging rates

Any official guidelines provided by the authorities

Tidal information

Past history of vessels of similar size touching the ground at the relevant berth.

2. After berthing

This would cover the actions which crew need to take to avoid any damage to the vessel or its machinery and other equipment. It would cover items such as changing over to high sea chest, 6-9 point manual sounding around the vessel to ascertain the depths, and bottom sampling. Bear in mind that soundings taken from the hand lead line may not be accurate if there is significant flow at a river berth. Mariners should therefore use echo sounder readings to verify and notify port authorities, if in doubt.

3. After vessel takes to ground at low tide

For structural strength and stability reasons, our recommendation is to cease loading if the vessel touches bottom. This is an important issue to highlight to the charterers as the vessel's stability is calculated in an afloat condition in the loading computer and the vessel will experience a virtual loss of stability upon touching bottom. This effect is particularly pronounced when loading deck cargo. If the vessel’s loading computer cannot calculate stability for the condition when the vessel sits on the ground, the vessel’s class society may be contacted for guidance on stability calculations.

The second most important thing is to ensure that the vessel’s hull is not breached. Crew will need to frequently monitor soundings in spaces such as double bottom tanks, duct keel, cofferdams, stool spaces and cargo hold bilges. The vessel may move laterally away from the berth upon taking ground and for that reason the moorings might need extra attention. The vessel’s sudden lateral movement can also cause damage to the ship and shore equipment such as the cranes and gangways.

4. After refloating

An underwater survey should be arranged to determine whether there is damage to the hull and steering system.

Case study 2: Damage caused by vessel’s lateral movement

In one of the Gard cases, the vessel moved a few metres away from the jetty upon taking ground. As a result, her mooring lines came under stress causing damage to the gangway and also to the jetty.

In this case, it was arguably the characteristics of the seabed which resulted in damage to the vessel and the jetty. However, damage could perhaps have been avoided by ordinary good seamanship. It is worth highlighting here that an unsafe condition must exist at the time of the commencement of the voyage. For example, if the slant of the seabed could be said to have been caused by silting and the absence of regular dredging, this could be considered an unsafe condition.

Case study 3: Damage to the vessel

During dry docking, it was noticed that there was damage to the rudder, shaft, shaft flange and the bearing. The vessel had been calling several NAABSA ports regularly in the months prior to dry docking. However, no underwater surveys of the bottom had been carried out by after any of these port calls. Nor was any bottom sampling done.

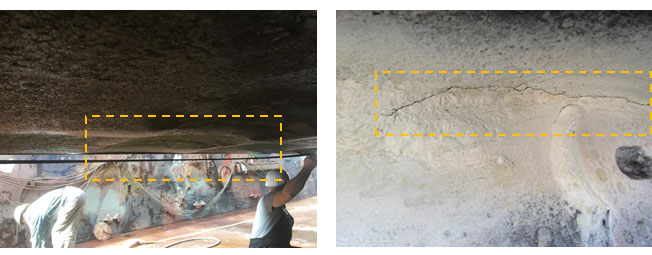

Left: Indentation on hull bottom, Right: Crack on rudder

Frame cracked in a ballast tank

In the above scenario, if it can be shown that the vessel damage was caused by an unsafe condition where she was ordered to lie aground, there may be a basis for owners to claim against the charterer. No contemporaneous surveys were done and this raises problems as the owners would have the burden of proof to show that damage to the vessel was caused by an unsafe condition. Without contemporaneous evidence, recovery for damage may be difficult. Again, this is why we recommend an underwater survey after refloating where and when visibility is sufficient to document damage.

NAABSA and your insurance - P&I and H&M cover

Gard’s P&I covers for owners and for charterers (including liability for damage to hull) would normally not be prejudiced so long as it is a customary trade under standard charter party terms and the Member or client complies with the relevant requirements. For vessels in NAABSA trade, owners are recommended to check whether the Hull and Machinery policy includes a clause that waives notification to the insurer but requires owners to obtain agreement from the charterer to indemnify the owner for damage caused to the vessel by grounding at berth. Charterers should be aware that accepting charterparty clauses that apply strict liability for damage to hull irrespective of negligent navigation would need to be approved by Gard for cover to remain intact. Thus, for owners and charterers, it is wise to check with their brokers and insurers when agreeing to NAABSA trade.

Recommendations

When calling a NAABSA port, a certain amount of due diligence is required not only from the crew members but also the owners’ shore management and charterers to avoid not only damage to the vessel and delays, but also straining the commercial relationship between owners and charterers. Both owners and charterers therefore need to be aware of the NAABSA clauses agreed to in the charterparty and their effect. So, what should owners and charterers bear in mind ahead of a voyage? We highlight key points below:

As Masters are generally less familiar with charterparty terms, owners/managers should highlight such clauses to Masters, to ensure that the crew are aware that the vessel may touch bottom at certain ports.

Charterers should clearly identify the nominated port as a NAABSA port in the voyage instructions and request an acknowledgement from the Master.

The Master should carefully read the voyage instructions, and the agents’ arrival message. The Master can request further information on the characteristics of the port from the agent.

Owners should have procedures to guide the crew on the risks of calling NAABSA ports and actions required by them to ensure operations are carried out in a safe manner.

Owners and charterers should, insofar as is practicable, agree to jointly carry out bottom sampling at the nominated port/berth. This should give both parties a clearer picture of the risks of touching bottom, and potentially avoid damage to the vessel, the costs of which charterers would likely end up being responsible for.

Owners should check their hull and machinery policy terms for any conditions to cover. Charterers entered with Gard should notify their underwriter when agreeing to non-standard and onerous NAABSA terms to ensure they remain covered for damage to hull.

Those members and clients with Defence cover may also consult with their Defence lawyer, regarding the legal effect of the NAABSA clause at the time of negotiation and fixing or during and after an incident where allocation of costs is in dispute.