Updated 10 April 2025 Seafaring has always been a dangerous occupation. Long voyages, extreme weather conditions, illnesses and accidents can take a heavy toll on the health of crew members – and – make it easy for the small mosquito to fly under their radar. As seafarers are also isolated from the usual source of medical care and assistance available to people on shore, the mosquito’s ability to rapidly spread deadly diseases to humans makes it a very dangerous adversary. Malaria and dengue fever are the most common mosquito-borne diseases today and the ones most likely to affect seafarers. However, sporadic and local outbreaks of other diseases, such as yellow fever, chikungunya and Zika, may also pose a risk to visiting seafarers.

Managing infectious diseases

Infectious diseases can cause life-threatening health problems for seafarers and lead to substantial costs and major disruption for maritime employers. Preventive measures are therefore essential. Infection may be transmitted by many means, including by food and water, from person to person, or by animal or insect bites. The main means of infection control on board ships are through implementation of effective personal hygiene measures. However, since mosquito-borne diseases generally do not spread from person to person - the virus or parasite needs a mosquito as its means of transportation – implementation of effective hygiene measures may simply not be enough. Supplementary measures, such as insect bite avoidance, preventive medication in the case of malaria, and vaccination programs, will be required.

The risk of contracting any infectious disease, and particularly a mosquito-borne disease, will depend on several ship and voyage specific factors and onboard requirements must be determined by assessing:

the route of the ship, especially the location of ports visited, length of stay and likelihood of exposure ashore either on shore leave or when joining or leaving a ship,

known health risks in the country of origin of seafarers and countries passed through en route to joining or leaving the ship, as well as

each seafarer’s role and work tasks.

It is a ship operator’s responsibility to establish an effective procedural system for, and create awareness on, the risk of infectious diseases in general, and mosquito-borne disease transmission in particular. It must be ensured that seafarers are familiar with the signs and symptoms of the most common mosquito-borne diseases, understand that these diseases are serious and potentially fatal, and implement prevention measures when their ship is destined for areas where there is a potential risk of being infected.

Mosquito-borne diseases affecting shipping – fast facts

The global burden Mosquitoes may be the deadliest animals in the world as their ability to carry and spread disease leads to hundreds of thousands of deaths every year. Major trade routes pass through areas affected by mosquito-borne diseases, putting seafarers at risk. Exposure to mosquito bites and the resulting rates of infection will vary within a single country and with the seasons. The latest official advice should therefore be checked every time a ship is destined for areas where there is a potential risk of mosquito-transmitted diseases.

At the time of writing, the WHO reports that:

Malaria alone causes more than half a million deaths every year. While malaria is found in tropical and subtropical areas of Africa, Asia, the Middle East and Central and South America, the WHO African Region carries a disproportionately high share of the global malaria burden. Globally in 2023, there were an estimated 263 million malaria cases and 597,000 malaria deaths in 83 countries. The WHO African Region was home to 94% of the cases and 95% of the deaths. Over half of these deaths occurred in four countries: Nigeria (30.9%), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (11.3%), Niger (5.9%) and United Republic of Tanzania (4.3%).

The incidence of dengue has grown dramatically around the world, with a more than ten-fold increase in the number of cases reported since the year 2000. The highest number of dengue cases ever recorded was in 2023 with over 6.5 million cases and more than 7,300 dengue-related deaths. While dengue has traditionally been found in tropical and sub-tropical climes, mostly in urban and semi-urban areas, rising global temperatures are allowing the mosquito to migrate further north and dengue circulation has now been reported from over 80 countries in all WHO regions. However, the Americas, South-East Asia and Western Pacific regions are still the most seriously affected.

Yellow fever and chikungunya are both diseases that can prove fatal and have both been the cause of epidemics in recent years. Yellow fever is primarily found in Africa and Central and South America. However, as yellow fever is fortunately preventable by an extremely effective vaccine, significant progress in combatting the disease has been made. As for chikungunya, the disease continues to spread but serious complications of this disease are not very common. Chikungunya is found mainly in Africa, Asia and the Americas but has also spread to Europe in recent decades.

The Zika virus was almost dormant for six decades until global outbreaks in 2015 were recorded in Africa, the Americas, Asia and the Pacific. Although cases of Zika virus disease has declined since 2017, transmission persists at low levels in several countries in the Americas and other endemic regions. While most people with Zika virus infection do not develop symptoms, an increased risk of neurologic complications is associated with Zika virus infection in adults and children, including Guillain-Barré syndrome, neuropathy and myelitis.

The nature of the diseases The mosquito that transmits malaria, the Anopheles mosquito, is active mainly at night, between dusk and dawn. Zika, dengue, chikungunya and yellow fever, on the other hand, are primarily transmitted through the bites of an infected Aedes mosquito which also bites during daylight hours. Zika can also be sexually transmitted from one person to another.

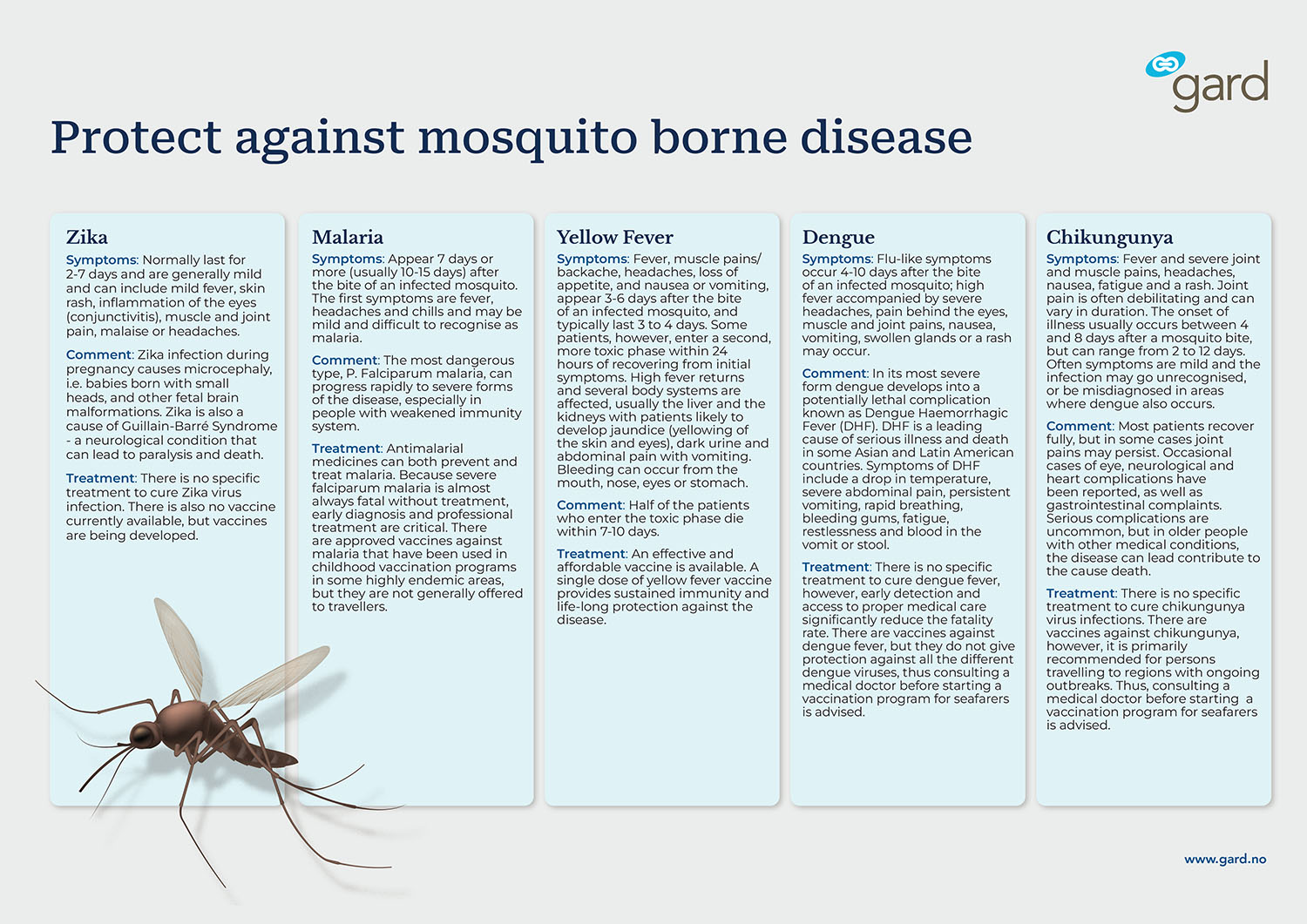

A seafarer infected by any of the common mosquito-borne diseases may initially experience mild non-specific symptoms similar to those of influenza and other febrile illnesses. However, as severity and treatment vary between the diseases, immediate medical attention should be sought to ensure early diagnosis. Information that may assist in diagnosis has also been published by the WHO and is reproduced below.

Click here to enlarge the above illustration.

Recommended precautions

Owners and operators with ships trading within mosquito zones should ensure that the crew onboard these ships are able to deal with the various challenges that these diseases can bring. As far as practicable, they should tailor make their own strategies for dealing with risks associated with infectious diseases and for mosquito-borne diseases in particular, the following should be considered:

Prior to visiting affected areas

Monitor the WHO website and similar sources for official advice regarding any ongoing outbreaks. Contact a medical practitioner if in doubt.

Review all the ports to be visited and evaluate the risk for each port. Consider the length of stay in an affected area, time spent at sea, in port and on rivers, as well as planned shore leaves by the crew.

Inform the crew about the risks and the precautions to be taken as well as actions to be taken if illness occurs at sea. Stress that a headache, fever and flu-like symptoms are always grounds for contacting the medical officer.

Ensure sufficient supplies of effective insect repellents, light coloured boiler suits, porthole/door mesh screens and bed-nets.

Consider, in close co-operation with a medical doctor and based on the ship’s expected exposure time in an affected area, if the crew should take a specific vaccine and/or an antimalarial drug. Considerations for the type of antimalaria drug to be used should include efficacy, local resistance patterns, simplicity of dosage schedule, and possible adverse effects of the medication.

Ensure that all crew members carry valid yellow fever certificates. As a precaution, check with the ship’s agent that local port health inspectors are aware of their country's official position regarding yellow fever vaccination requirements and will recognise the amended IHR and yellow fever vaccinations with lifetime validity.

Stay up to date on new vaccine programs that may be relevant for seafarers.

During a visit to affected areas

Implement measures to avoid mosquito bites, e.g. wear protective clothing, stay in air-conditioned screened accommodation areas, use undamaged insecticide-treated bed-nets in sleeping areas. Use effective insect repellents on exposed skin and/or clothing as directed on the product label and when using a sunscreen, the recommendation is to apply sunscreen first, followed by repellent.

If crew members are taking anti-malarial drugs, implement a method of control to ensure they take the medication at the prescribed times, e.g. via a log book.

Remove pools of stagnant water, dew or rain in order for the ship not to create its own mosquito breeding grounds. Pay particular attention to areas such as lifeboats, coiled mooring ropes, bilges, scuppers, awnings and gutters.

After a visit to affected areas

Seek medical advice over the radio, particularly if malaria or dengue is suspected on board. Normally, the ship is in port only for a short time and will most probably be back at sea when symptoms are noticed due to an incubation period of several days.

Place the patient under close observation and administer the necessary onboard care, preferably in close co-operation with a medical doctor. Normally, this will include bed rest, plenty of fluids, and easing of symptoms such as fever and muscle pain. Always consult a doctor before giving antimalaria medication and avoid the use of NSAIDs unless dengue can be ruled out, to reduce the risk of bleeding complications. Evacuation may be the only solution if the patient’s condition does not improve.

As a Zika infection during pregnancy can cause microcephaly, i.e. babies born with small heads, all seafarers concerned about a pregnancy, males and females, are advised to consult a health care provider for counselling after exposure to Zika virus.

Additional resources

Prevention requires vigilance so stay up to date! For medical officers, we recommend consulting the diseases section of the Mariners Medico Guide app to obtain up to date medical information and treatment support for different mosquito borne diseases. General preventive measures are also highlighted in the injury section of the guide addressing insect bites and stings.

Here are some additional recommended sources of information:

Detailed information about each mosquito-borne disease - its characteristics, treatment, prevention, geographical distribution and recent outbreaks - is available via WHO’s “Health topics”.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) provides similar information via its “Disease & Conditions A-Z Index”.

The CDC’s general “Destination List” can be a good starting point for a voyage specific risk assessment related to mosquito-borne diseases.

The International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assistance Network (ISWAN) offers guidelines and posters for malaria prevention onboard merchant ships.

National governments may also publish safety alerts concerning seasonal outbreaks of the diseases on their “safe travel” websites. Relevant information can also be obtained from medical doctors and local vaccination offices.