Now that the Ocean Opportunities Report has been finished, Gard’s contributors reflect on what they learned along the way.

Global Goals, Ocean Opportunities - reflections on public and private ocean governance

Published 06 June 2019

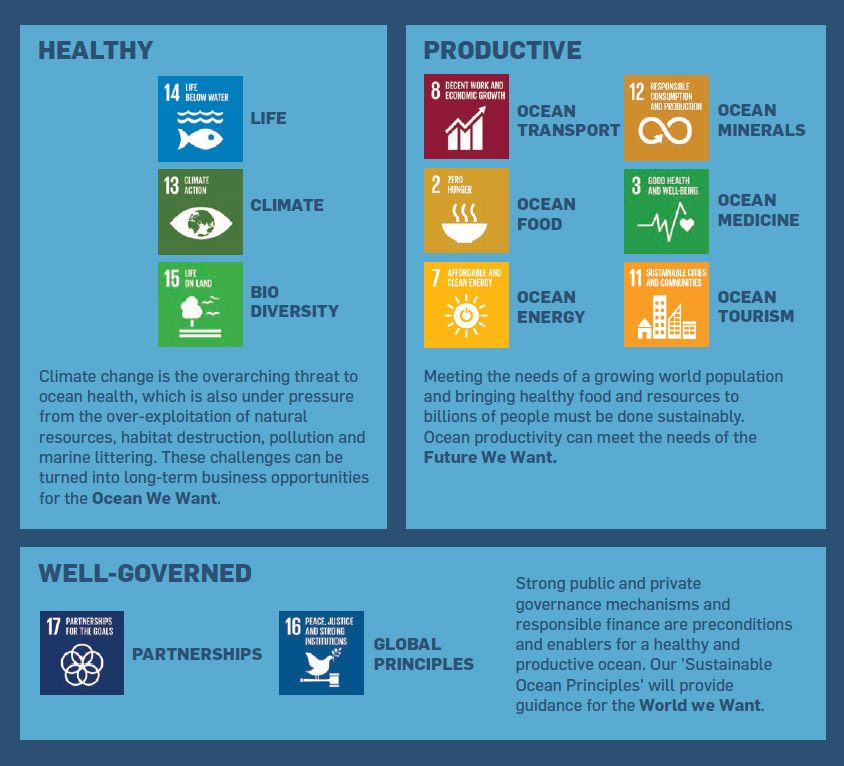

Gard participates in the United Nations Global Compact Action Platform for Sustainable Ocean Business. The Platform is taking a comprehensive view of the role of the ocean in achieving the UN’s 17 Global Development Goals. The aim is to explore attractive, viable solutions and best practices for sustainable use and management of humanities’ greatest ’common’ - our ocean. In December 2018, Gard was asked to join the editorial board for the Ocean Opportunities Report and Erika Lindholm and I took on the challenge. The report was released this week as part of the Nor-Shipping Conference in Oslo. Rather than summarize the report, we will instead describe our thought process in writing about ocean governance including some of the preliminary thoughts that did not reach the final version.

The Report identifies ocean businesses by sectors – Ocean Transport, Ocean Food, Ocean Energy, Ocean Minerals, Ocean Medicine and Ocean Tourism. At an earlier stage Marine Insurance was considered a business sector but in the course of the discussions, we suggested that marine insurance is not a direct ocean business but an ’enabler’ of all the others. The concept comes from Gard’s mission statement: “Together we enable sustainable maritime development.” So, the editorial board agreed that insurance (as well as finance and classification societies) would fall within a separate chapter about ocean governance.

© Ocean Opportunity Report

It was March 2019 with the release date in June looming and Erika and I had set ourselves up for drafting the governance chapter of the report. We felt that our first task was to define what was meant by ’governance’. While used broadly and seemingly understood widely, the term was not easy to define. Try it yourself – google it and see if you can come up with a comprehensive definition. We were able to draw upon the Platform’s first report from September 2018 called Mapping Ocean Governance and Regulation which introduced the concept of public and private ocean governance. We defined governance in the Opportunities Report:

“Governance includes the rules that determine the rights and responsibilities of those using the ocean for economic activities. It also encompasses the institutions that create such rules, enforce them, and provide dispute resolution processes and forums. Governance is both a public and private sector activity. Public governance is regulation through national and international law and institutions while the private sector establishes industry standards and principles, due diligence processes, and procurement rules.”

Now to find an example of the interaction between public and private governance and the role insurance plays in support of international conventions. We thought about the role of P&I clubs in filling the mandatory insurance requirement under international conventions that provide for strict liability and mandatory insurance for pollution and provided a case study in the draft:

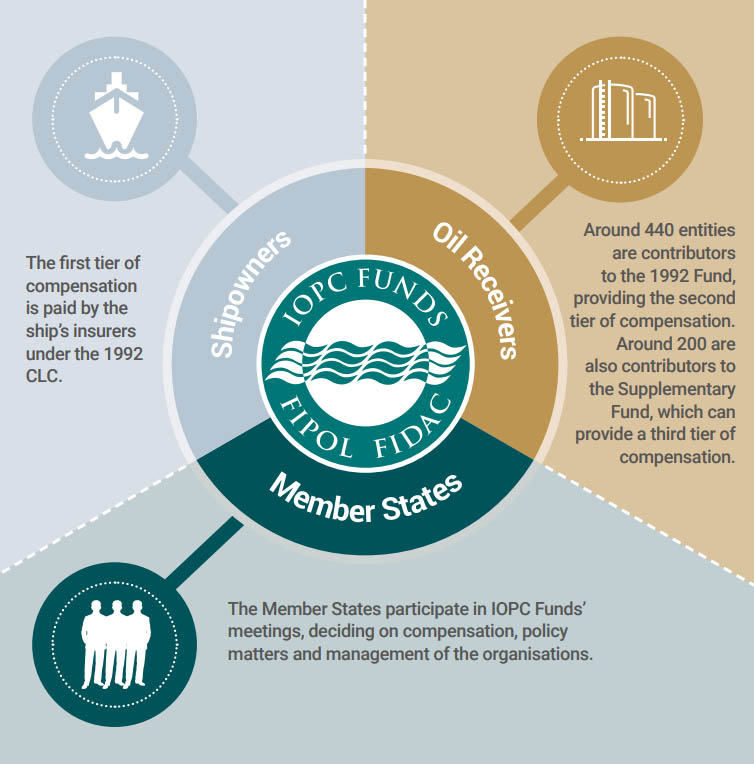

In March 1967, the supertanker Torrey Canyon ran aground off Britain’s Cornish coast and spilled an entire cargo of crude oil – some 80,000 tons of which spread along the British and French coasts. The disaster resulted in two international liability and compensation treaties: The International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage 1969 (CLC 69) and the International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage 1971 (1971 FUND). The CLC established strict liability of shipowners for spills of persistent oil carried as cargo and the requirement for compulsory insurance. The CLC and Fund conventions established a cost sharing between the shipowner and their P&I Clubs on the one hand and the oil receivers on the other. This regime exists today in the form of the 1992 International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund and the accompanying 2003 Supplementary Fund. The Fund Conventions provide compensation in excess of the CLC limitation amount based on ship tonnage that makes up the first tier of compensation.

Funding then for tanker spills of persistent oil is effectively split between Liability Insurers for the first tier and oil receivers as contributors to the Fund.

© IOPC

As of 31 December 2018, 137 States have ratified the current version of the CLC – the 1992 Civil Liability Convention, and 115 States have ratified the 1992 Fund Convention.

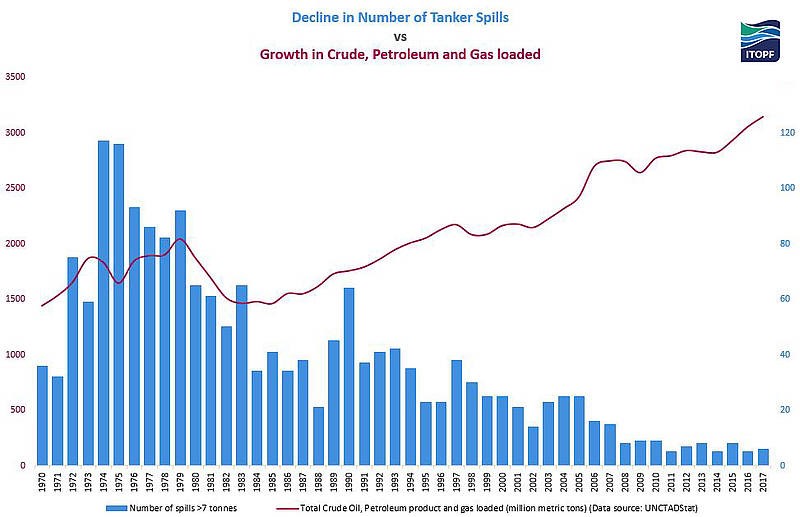

*Since a high in the 1970s, the incidence rate of tanker spills has dropped steadily despite a rising volume in carriage of crude, petroleum and gas. *

© ITOPF

The reduction can be explained by implementing international conventions, focus on quality from shipowners and oil companies and implementation of new ship designs.

Our proposed case study showing the role of P&I insurance within the public governance regime set by the CLC and Fund Conventions did not make it into the Ocean Opportunities Report due to space constraints. In the spirit of sustainability, we are pleased to recycle it here.

While researching the intersection between insurance and public governance, we realized that there was much more to the private governance story following the Torrey Canyon spill. The beginnings of strict liability and reliable insurance for tanker spills was voluntary action by industry. Shortly after the Torrey Canyon disaster, seven major oil companies, who owned a high proportion of seaborne oil cargoes and operated a significant part of the world’s tanker fleet, agreed upon the idea of an industry initiative in which tanker owners voluntarily accepted strict liability to pay compensation for oil pollution damage up to an amount limited by the tonnage of the tanker from which the spill originated. The initiative was formalized in an agreement known as TOVALOP (the Tanker Owners Voluntary Agreement Concerning Liability for Oil Pollution). The International Group P&I Clubs agreed to extend cover for pollution liability under the agreement even though it was voluntary and not imposed by law.

The TOVALOP Agreement became fully effective in October 1969, when it had secured 50 per cent of the world’s tanker tonnage as Members. Just six months later, this had risen to 80 per cent. A supplementary agreement called CRISTAL evolved from this initial voluntary agreement to provide a second layer of compensation payable by cargo owners.

These two voluntary schemes provided the basis for the development of the CLC and Fund Conventions and operated as an interim measure pending the widespread ratification of the Conventions. TOVALOP and CRISTAL have been retired and replaced by the CLC and Fund Conventions but the International Tanker Owners Pollution Federation (ITOPF) which was originally set up to administer the schemes continues to provide expert support in promoting effective spill response. https://www.itopf.org.

The United Nations Global Compact call to action to address today’s critical challenges to ocean health requires companies to step up as stewards of sustainable ocean practices. The public and private cooperation in dramatically reducing ship source oil pollution from the high point in the 1970s can inspire us to take concerted action today against plastic pollution, over-fishing and green-house gas emissions that have been identified in the Ocean Opportunities Report as some of the principle threats to ocean health and human well-being.