Can owners accommodate a charterer’s request to switch bills of lading?

Published 28 February 2018

Negotiable bills of lading are fundamental to trade. As documents of title, they are essential to the sale and carriage of commodities. The holder in due course is entitled to delivery of the cargo as described by the negotiable bill of lading. This right goes to title as well as quantity and description of the goods. In our guidance, we have focused on the obligations of the vessel owner and Master with respect to the form and content of bills of lading, as well as the risks arising from inaccurate description and mis-delivery due to unavailable originals or multiple sets of bills.

In addition to vessel owners, Gard insures P&I liabilities and provides Defence cover to intermediate charterers as well as cargo traders and we can sometimes find ourselves providing advice from different perspectives, depending on the position of the insured in the charter relationship. One area of dispute and confusion between parties in a charter chain involves a request to switch new bills of lading for the original bills of lading. Our aim in this article is to address this practice and to provide advice considering the needs of the trader, the disponent owner and the vessel owner.

Why switch bills of lading?

There are many reasons for wanting to switch bills of lading. For example:

The original bill of lading quantity is to be split into smaller parcels, with each parcel documented by its own bill of lading. This is sometimes referred to “splitting bills of lading”.

A series of original bills of lading are to be consolidated where different productsare blended, with that new blended cargo documented by its own bill of lading.

The original bill of lading may name a discharge port which is subsequently changed, as the goods have been sold or resold on the water, so a new set of bills of lading are requested naming the new discharge port.

A commodities trader does not wish the name of the original supplier and shipper to appear on the bills of lading, and so a new set is requested naming the trader as the shipper. This protects the trader from being cut out of the sale opportunities in subsequent transactions by revealing the trader’s sources.

The original bills of lading may not conform with the requirements for the bills of lading under the relevant letter of credit, in which case, if the deficiency is not waived by the issuing bank, the seller may request that new conforming bills of lading are issued by the carrier.

There may also be cases where switch bills of lading are requested for illegitimate reasons such as the following:

To hide the shipper’s identity or the origin of the cargo because they are a sanctioned entity.

To alter the date of shipment so that it falls before the last shipment date under a letter of credit.

To alter the nature of the cargo, as perhaps the bills of lading are claused and “clean” bills of lading are required for presentation under the letter of credit.

The risks and dangers are clear: circumventing applicable sanctions or misrepresenting facts that may constitute fraud. For this reason, an owner or carrier must exercise due diligence to understand the reason for a request to switch bills, and a trader or charterer should be prepared to fully explain its request.

Switching the identity of the shipper – meeting the trader’s commercial needs

An increasingly common reason for switching bills of lading is because a party is selling the cargo on and they do not want their counterparties to be able to identify each other, and cut the intermediary party out of the sale contract string.

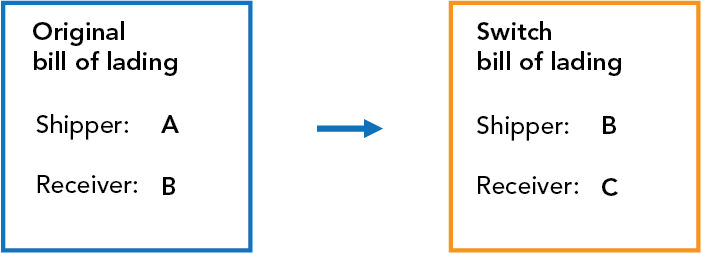

For example, if Party A is the shipper, Party B is the trader/original consignee, and Party C is the buyer, then Party B may request the vessel owner to switch the bills of lading so that they show Party B as shipper instead of Party A, and with Party C given as Consignee instead of Party B. In this way, Party A and Party C never learn each other’s identity, which prevents them from dealing directly in the future, and thereby protects Party B’s ability to earn profit on the re-sale. This is a legitimate commercial reason to switch bills of lading – the aim is not to defraud Party C about the origin of the cargo, but to protect Party B’s business relationships.

Insight SwitchBill

Vessel owners are normally told that they must not issue bills of lading that they know to contain inaccurate information, or (amongst other things) they risk prejudicing their P&I cover. The identity of the party that shipped the cargo on board a vessel is a matter of fact. The name of the shipper given in a bill of lading may therefore be thought to be a representation which, if inaccurate, could give rise to potential claims for damages against the vessel owner/carrier.

On one analysis that is right, however, it is hard to think of many situations where the value of a cargo is affected by the identity of the shipper. The price could depend on many variables, such as condition, quality, date of shipment and origin – but rarely the name of the party that shipped the cargo on board. The name of the shipper alone is unlikely to give any accurate indication of the quality or origin of the cargo, because they could have bought from any number of sources. Further, there will often be no reason why Party B could not have purchased the cargo from Party A before it was loaded on board, rather than after, in which case Party B would in fact have been the shipper. The fact that Party B bought the cargo after shipment, but the bill of lading suggests that they bought it before is unlikely to cause the end-buyer losses. Indeed, as a matter of the sale contract string, while the original shipper is what would be understood as the party that ships the goods, each subsequent seller in the sale contract string procures the shipment of goods under their sale contract with a buyer.

An exception would be where there is no legitimate business reason for the change – for example where the identity of the actual shipper makes the cargo less valuable, e.g. because they are a sanctioned party. It may well be difficult to sell cargo if the bill of lading shows a sanctioned entity as shipper. Seeking to hide the fact by changing the bills of lading may well enable a sale, but it could also cause an innocent third party to suffer losses when the sanctions issue is later revealed. In this case, even a LOI from a charterer may offer the owners no right of recourse.

For this reason, we recommend that when vessel owners or contractual carriers receive a request for switch bills, they should examine the situation and ask any necessary questions to check if there are legitimate reasons for the switch bills.

Furthermore, it would normally be sensible to ensure that the original shipper has consented to being removed from the bill of lading. A bill of lading is evidence of the contract of carriage, and if the contract is going to be changed to remove and replace a party, their consent (or confirmation of non-objection) should be obtained first. In some cases, the party requesting the switch bills of lading may be reluctant to provide direct evidence of such consent, but if their request is above board, they should be able to give reasonable satisfaction on these points.

Even if it appears that a request to switch bills of lading is sound and has been consented to by the shipper, a vessel owner would still normally want to obtain a suitably worded Letter of Indemnity before agreeing to the switch as there are risks with any cancellation and re-issuance of bills of lading.

What date and place of issue should be used in the switch bills of lading?

Bills of lading should state the date and place at which they have been issued. The date of issue is important because it is usually assumed to be the date of shipment, which in turn can affect the value of the cargo. The place where the bill of lading has been issued can affect which cargo liability regime applies to the contract of carriage. See for example Article X of the Hague-Visby Rules which provides that the regime applies when the bill of lading is issued in a signatory country.

It seems that when switch or other replacement bills of lading are issued, the practice is sometimes for the new bills of lading to be issued with the same date and place of issue as the old bills of lading – even when it is not true. That may be understandable from a commercial point of view (e.g. if a party does not want to reveal the fact that the bills have been switched), however, it is not the correct legal approach. If the replacement bills of lading are issued showing an inaccurate issue date, then it is a misrepresentation. Replacement bills of lading should be dated to show when they are actually issued. As Banks LJ said in Guaranty Trust of NY v Van Den Burghs (1925) 22 LLR 447 at p.455:

“I am sorry that the bills of lading were issued "Dated at Manila this 24th day of September, 1924,” because that was a deliberate untruth. They should be dated in New York on Dec. 16, 1924, acknowledging receipt of a cargo of oil in Manila on Sept. 24, 1924,”

A common assumption seems to be that the date of the bill of lading and place of issue must always be the date of shipment and port of loading, but that is a misunderstanding.

*(a) * The date of issuance can be different to the date of shipment

A bill of lading may contain both (i) a date of shipment, and (ii) a separate date showing when it was actually issued. The only requirement is that both dates are sufficiently clear so that a third party can understand the true position. The possibility of two dates is supported by the UCP 600, which provides in Articles 20(a)(ii) and 22(a)(ii) that:

The date of issuance of the bill of lading will be deemed to be the date of shipment unless the bill of lading contains an on-board notation indicating the date of shipment, in which case the date stated in the on-board notation will be deemed to be the date of shipment.

*(b) * The place of issuance can be different to the place of shipment

Bills of lading can be issued somewhere other than the port of loading. For example, an agent may have been authorised to sign bills of lading on behalf of the Master, but the agent’s office is not located at the load port. Replacement bills of lading may also be issued at a bank or a trader’s office a long way from the loadport. These arrangements are perfectly acceptable if they are accurately recorded. Many of the common bill of lading forms have been prepared to allow this, and the possibility of it is reflected in the Hague/Hague-Visby Rules (Article X, Rule (a)).

We do sometimes see bills of lading that are said to be issued somewhere “as at” or “as if” the loadport – for example “Hong Kong as at Port Hedland”. The intention is presumably to accurately record where they were actually issued, but to also try to minimise the impact of issuing the replacement bills in that other place. The effect (and efficacy) of such wording is uncertain, but we do not think that its use is problematic in itself.

Clauses requiring the issue of switch bills of lading

It is becoming common to see a clause in a charterparty that requires the owner or disponent owner to allow the charterer to switch bills. Such a clause should include wording that substitutes for an LOI – an indemnity in exchange for agreeing to allow switch bills. This however, does not relieve the owner and disponent owner from exercising due diligence to ensure that the reason for the switch is legitimate. There is no obligation to agree to switch bills if the reason is illegitimate and an indemnity provision in the charterparty will offer little opportunity for recourse if the switch was to perpetrate a fraud or hide a sanctioned entity.

As a matter of practice, it is important for intermediary parties to note that agreeing to accommodate the sub-charterer’s request to switch bills in a sub-charter may put the disponent owner in a difficult spot if the charterparties are not back-to-back because the Master is not obliged to agree to the disponent owner’s ad hoc request.

Practically speaking, if the same clause is not agreed in each charterparty up and down the chain, it is best to have no clause at all, as it is ultimately the decision for the Master and the risk of a mis-match is removed.

Switching bills of lading against a letter of indemnity

A vessel owner would normally require an LOI to be issued prior to the cancellation and replacement of a set of original bills of lading – even if this is done by way of the charterers invoking the LOI under a specific clause in the charterparty.

We recommend that any LOI for switch bills of lading should set out the process of cancellation of the original bills of lading, and specify the exact changes that are being requested in the new bills of lading (ie. the names that are being changed), and also the actual date and (if different) place of re-issuance. If the LOI contains no reference to the new date/place of issue then the requesting party may assume that they have been authorised to issue the switch bills of lading with the (now inaccurate) date/place of the cancelled original bills of lading.

However, an LOI is not a silver bullet to all the issues. An LOI does not reinstate P&I cover, so it is only as good as the party that gives it. Furthermore, where there is fraud or illegality, the LOI may be unenforceable and conceivably, the contract of carriage may be unenforceable. Gard does offer limited cover for LOIs for delivery without production and changing the discharge port and other risks outside of P&I cover. This additional product does not cover liability for mis-delivery but instead covers the credit risk to the Gard insured that the issuer of the LOI is unable to perform.

The practicalities

There is no reason in principle why a Carrier or disponent owner should not agree to switch bills of lading. However, it should be diligent:

Check that the reason for the request is legitimate. Be aware that certain information must not be changed, such as the date of shipment or condition of the cargo.

Ensure that all relevant parties to the contract of carriage evidenced by the bill of lading consent to the alterations prior to any surrender and re-issue.

Consider whether the amendment will affect parties who have or may rely on the representations in the bill of lading.

Ensure that the original bills of lading are surrendered and cancelled prior to any re-issue in order to avoid having multiple sets of bills of lading in circulation.

Obtain a suitably worded Letter of Indemnity. Intermediate time charterers should insure that an LOI provided up the charter chain is at the least back-to-back with the LOI provided by the sub-charterer.

Traders or other parties who request switch bills of lading should be ready to give a full explanation of the reason for their request. Disputes and delay will be avoided or reduced if the carrier can see that the request is legitimate and comfort is provided by a suitable LOI. Also, consider alternatives, so if the issued bill of lading does not conform to the letter of credit requirements, ask the counterparty to waive the deficiency. If all other solutions fail, only then approach the carrier.

In sum, tensions between owners, disponent owners and traders over requests to switch bills can lead to delay and disputes that can be avoided by understanding the business reasons for the request and pre-planning by the use of charterparty clauses with indemnity provisions. Remember, even with a charterparty clause requiring it, the owner or disponent owner is not obliged to switch bills of lading if to do so is illegitimate, so traders requesting switch bills should be ready to provide information necessary for the counter-party to determine the reason for the request in each instance.

We thank Tom Rodd of Stephenson Harwood, London for his assistance with this article.